Introduction

As an introduction, watch this movie from the KhanAcademy.

If the movie does not play in this window, or you would like to see it in a window of alternate size, download it from this link.

Opening of Voltage Gated Channels Produces Action Potentials

The subunits of voltage-gated ion channels change conformation in accordance with membrane potential. This can result in the opening of a pore that allows a specific ion to pass through the membrane.

Two types of voltage-gated channels play a role in producing action potentials: those that allow sodium to cross the membrane (voltage-gated sodium channels) and those that allow potassium to cross the membrane (voltage-gated potassium channels).

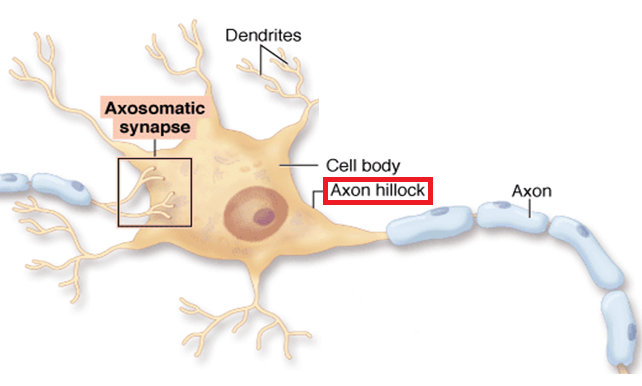

Voltage-gated channels are not usually present in the dendrites or the soma, but are concentrated in the initial segment of the axon (axon hillock). Both inhibitory and excitatory postsynaptic potentials are summed in the axon hillock. If the inside of the axon hillock is sufficiently depolarized (becomes less negatively charged), the Na+ channels open and allow Na+ to enter the neuron. Since Na+ concentration is low inside the cell (due to the actions of the sodium-potassium pump) and the inside of the cell is negatively charged, Na+ rushes from the outside to the inside of the cell.

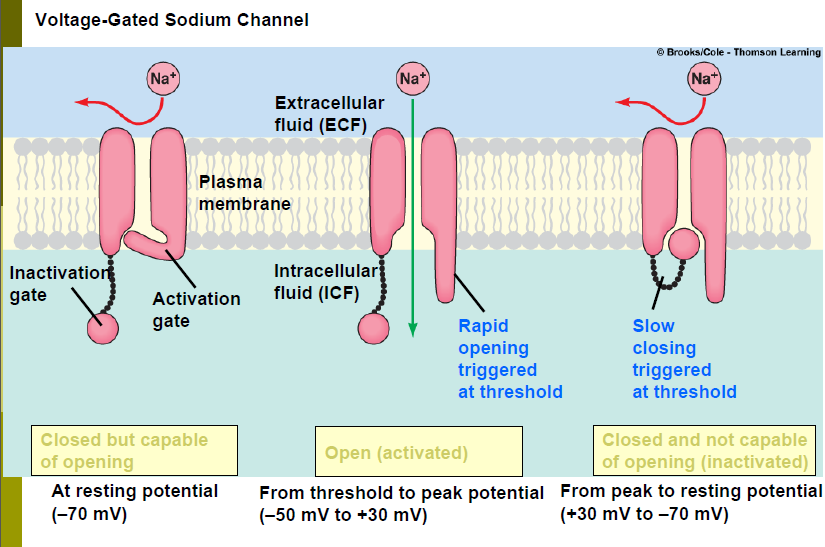

Voltage-gated Na+ channels have two gates: an activation gate and an inactivation gate. The activation gate opens quickly when the membrane is depolarized, and allows Na+ to enter. However, the same change in membrane potential also causes the inactivation gate to close. The closure of the inactivation gate is slower than the opening of the activation gate. As a result, the channel is open for a very brief time (from the opening of the activation gate to the closure of the inactivation gate).

Another important characteristic of the sodium channel inactivation process is that the inactivation gate will not reopen until the membrane potential returns to the original resting membrane potential level. Therefore, it is not possible for the sodium channels to open again without first repolarizing the nerve fiber.

Note that after the resting membrane potential is restored, a short period elapses before the inactivation gates of the voltage-gated Na+ channels open. While the inactivation gate is closed, it is impossible for a new action potential to be elicited. This period is called the absolute refractory period.

As noted above, the voltage-gated K+ channels close slowly after the membrane has been repolarized. Consequently, the K+ conductance is higher (and the neuronal membrane is more hyperpolarized) at the end of the action than in the normal resting state. As a result, it is more difficult to generate the amount of depolarization needed to open the activation gates. This period of higher K+ conductance at the end of an action potential results in a relative refractory period, during which it is possible to elicit an action potential, although a strong excitation is need to do so.

Saltatory Conduction in Myelinated Axons

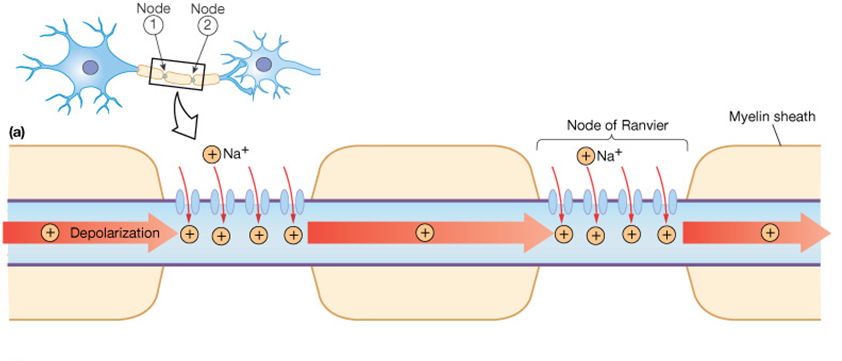

Many neurons have myelin surrounding the axon. Myelin is a fatty white substance deposited by glial cells that insulates the axon, decreasing the leak of current through the axonal membrane. The voltage-gated channels described above are located between adjacent myelin sheaths. An unmyelinated area of membrane at the gaps between myelin sheaths, which contains voltage-gated channels, is called a node of Ranvier.

Myelination allows a bolus of sodium that enters through voltage-gated Na+ channels to move quickly down the axon without leaking out very much. Another action potential occurs at the next node of Ranvier down the axon, refreshing the process. As such, the action potential appears to "leap" between the nodes of Ranvier, in a process called saltatory conduction.

Saltatory conduction allows electrical nerve signals to be propagated long distances at high rates without any degradation of the signal. In addition, the process is energy-efficient, as perturbations in the normal compartmentalization of Na+ and K+ only occur at the nodes of Ranvier. Bear in mind that after an action potential, the sodium-potassium pump has to restore the normal ionic balance across the membrane. Minimizing the need to do this reduces ATP expenditure.

Now you should be able to understand that the refractory period for axons described in the section above has a very practical physiological purpose: it assures that action potentials move in one direction down the axon. When an action potential is generated at one node of Ranvier, the previous node is still in a refractory period. Although sodium ions entering at a node diffuse in both directions down the axon, the previously-activated node cannot generate an action potential. This is key in assuring that an excitatory input to a neuron does not result in a reverberating series of action potentials.

Unmyelinated Axons Conduct Action Potentials Slowly

In contrast to myelinated axons, unmyelinated neurons must "refresh" the action potential in every successive patch of membrane. Thus, a repeated entry of Na+ ions and efflux of K+ ions occurs down the axon. The ionic redistribution is restored to the resting state by the sodium-potassium pump, but this requires a large amount of energy.

This may be the reason why unmyelinated axons have a small diameter. If an unmyelinated axon was of large diameter, the surface area would be large and many voltage-gated channels would be needed on the surface. When an action potential occurred, the movement of ions would be large, and a tremendous amount of ATP would be needed to fuel the activity of the sodium-potassium pump to restore ionic balance.

Two major factors govern how quickly an action potential moves downs an axon:

- its diameter

- how heavily myelinated it is

In general, the largest axons are also the most heavily myelinated, and propagate action potentials very rapidly. The smallest axons are unmyelinated and propagate action potentials slowly.

How do the amount of myelination and the diameter of an axon determine its conduction velocity?

Let's turn to the KhanAcademy for an explanation.

If the movie does not play in this window, or you would like to see it in a window of alternate size, download it from this link.

Some Neurons Are Weird

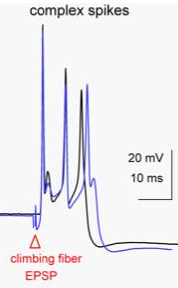

Although the action potentials of most neurons resemble those described above, some neurons have action potentials with different properties.

As an example, cerebellar Purkinje cells produce complex spikes, which are very broad and complicated action potentials.

As shown to the left, the complex spike has a duration of almost 10 msec. A complex spike is characterized by an initial prolonged large-amplitude spike, followed by a high-frequency burst of smaller-amplitude action potentials. The duration of complex spikes is due to the presence of P-type voltage-gated calcium channels, whose opening contributes to the generation of the action potential.

In general, voltage-gated calcium channels open and close slowly, resulting in a prolonged movement of ions. This generates a long-duration action potential.